I’m not counting my chickens before they hatch, but I have a REALLY good report to bring you.

At the end of the day, after the Jury sent TWO notes to Judge Merchan and then he sent them home for the day, reports are out saying the Trump Team is appearing happy and animated, laughing and smiling.

The reverse for the Judge and the Prosecution, who are reported to be increasingly tense and agitated.

Take a look:

BREAKING: Trump's team was laughing and smiling by the conclusion of today's jury deliberation while the prosecution looked nervous

The judge sent the jury home early because he knows something beautiful may be brewing for Trump

Tomorrow we could get a "NOT GUILTY" verdict pic.twitter.com/7yFof3YGfv

— George (@BehizyTweets) May 29, 2024

And here from my friend Bo Loudon:

🚨OUTRAGED MERCHAN JUST SENT THE JURY HOME AFTER GIVING THE IMPRESSION THEY WON'T CONVICT TRUMP.

Even though a unanimous decision is NOT NEEDED, Judge Merchan appeared outraged at jury notes given to him.

Team Trump was seen laughing and smiling.

Share to make this go viral! pic.twitter.com/9mnsLDUtPb

— Bo Loudon (@BoLoudon) May 29, 2024

But it’s not just those reports….

Here is NBC News confirming:

So, isn’t the Judge supposed to be neutral anyway?

That’s strange!

The Jury questions and the fact there is no verdict yet seem to be pointing towards good news for President Trump:

🚨BREAKING: Just three hours into deliberations, the jury has come back to Judge Merchan with multiple questions. This could be a good sign for Trump, suggesting a holdout in the jury pool. pic.twitter.com/6Vr1o3N7Eh

— Charlie Kirk (@charliekirk11) May 29, 2024

Is Judge Merchan sending them home because he is frustrated with them?

The attorney on Newsmax says it is highly irregular for them to be sent home so early:

Jury has been sent home for the day….An attorney on NewsMax literally GASPED when she heard the news. Totally abhorrent behavior by the Judge, jury should deliberate into the evening. #Trump pic.twitter.com/w2pDsGT7kF

— Dr. Yvonne Vosburgh (@YvonneVosburgh) May 29, 2024

Or is this just like when we all just stopped counting the votes on election night in 2020 so they could scramble and roll in more boxes of ballots?

Was this already starting to go badly for Merchan and Bragg so they had to stop it early?

Here was our earlier report:

UPDATE: Jury Sends SECOND Note To Judge Merchan, Here’s What It Said — You Have To See This

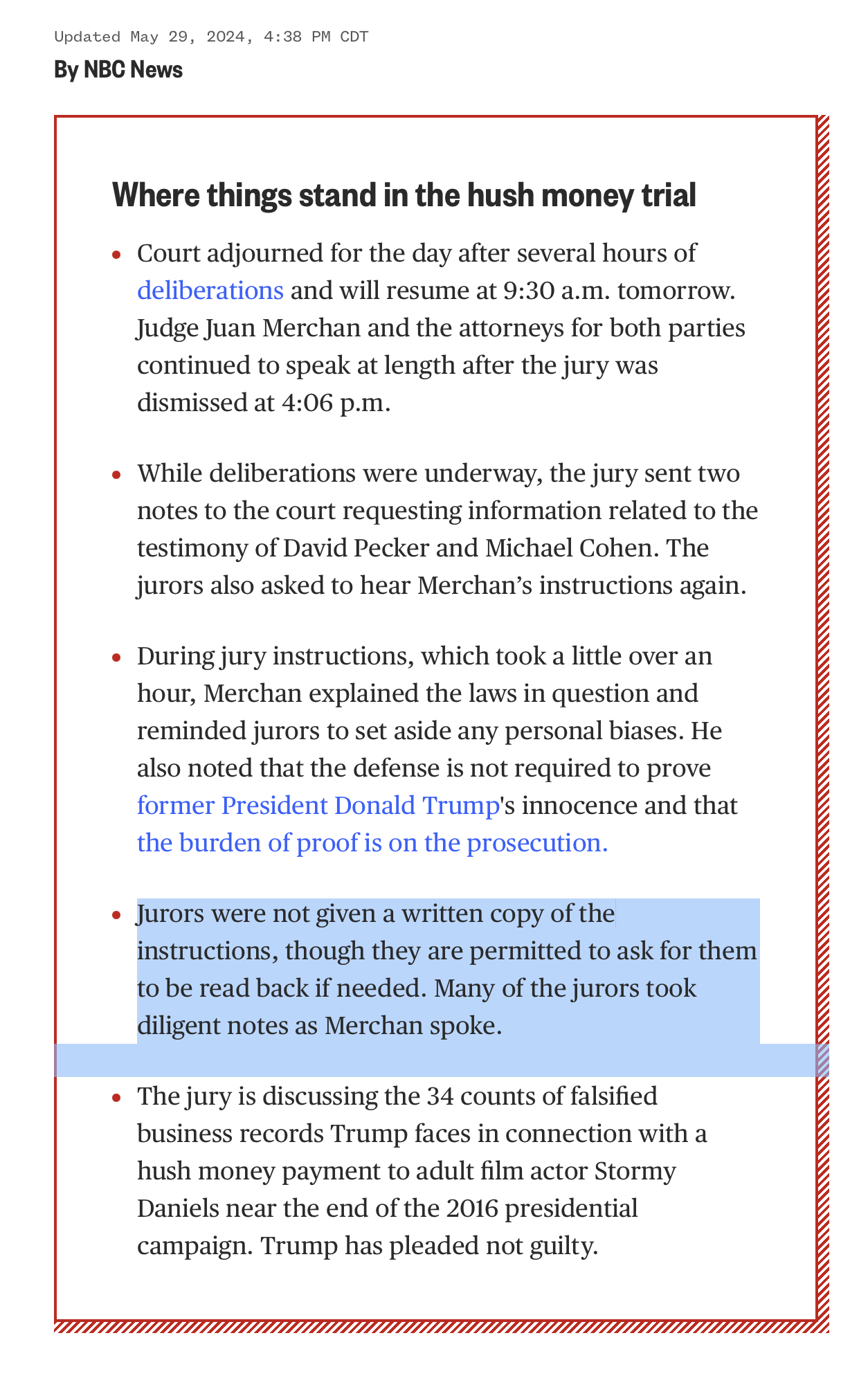

The Jury has been sent home for the day with no verdict, but that’s not before they sent TWO notes to the Judge:

🚨 #BREAKING: NO TRUMP VERDICT TODAY

The jury has now been dismissed, and will reconvene tomorrow at 9:30am

They’ve requested a read back of jury instructions, signaling that there is potentially strong disagreement within the jury as to the standards here

This case should… pic.twitter.com/LhAEn2cFoD

— Nick Sortor (@nicksortor) May 29, 2024

What is a note to the Judge?

It’s when the Jury is deliberating and has a question about something or needs clarification.

In this case, after only a few hours of deliberation, the Jury has already send two notes.

But here’s where it gets really interesting and why I say this is insane….because the notes are related to the Jury instructions.

Per Fox News, the Jury is asking to “rehear his jury instructions”.

Take a look at this from Fox News and then I’ll explain why this is quite literally “insane”:

And in case anyone else doubts this (I would not fault you, it is so crazy it’s hard to believe it could possibly be true), here is a second source, NBC:

Ok, so I’m not a legal expert, I just play one here on the Internet, but it is certainly my understanding that Jury Instructions are almost always printed out and GIVEN to the Jury.

Perhaps we can get some attorneys to comment down below and let me know if I’m off-base, but I have never in my life heard of a Jury only being READ ALOUD the Jury Instructions and not being given a copy.

It’s no wonder they are confused and already asking for additional information.

Even CNN’s legal expert is saying this is extremely bizarre:

An attorney on CNN can't believe how Judge Merchan handled jury instructions

"The jury must be overwhelmed. To have all of these instructions read to them without them getting a copy… the lawyers were not able to discuss instructions in their closings… which I find bizarre" pic.twitter.com/dsiH6YNosK

— johnny maga (@_johnnymaga) May 29, 2024

Here is “Crypto Lawyer” who I assume is an actual lawyer confirming that this is extremely strange:

Judge Merchan is making this very difficult on the jurors. If you have ever read jury instructions they are very complicated with legalese and precise definitions.

Having a jury go deliberate on 34 counts with no jury instructions is ludicrous. The jury instructions should be… https://t.co/UlIOBzySBU

— CryptoLawyer (@CryptoLawyerz) May 29, 2024

It’s completely dumbfounding to understand how a Jury is supposed to make sense of this without being able to READ and RE-READ and RE-READ again the instructions:

🚨Corrupt Judge Bans Jury Instructions🚨

Judge Merchan has ruled that the jury will not be given copies of the instructions but can ask for them to be read to them again. How is the jury supposed to properly deliberate on 34 felony counts… How did we let it get this bad. pic.twitter.com/zTo4wyULLo

— Elephant Civics (@ElephantCivics) May 29, 2024

Even “Steve” with his Ukraine flag in his Twitter profile is admitting this is insane:

Trump trial jury is asking for the instructions again

Did anyone ever SANELY / REASONABLY explain why the instructions cannot be handed as a copy to each juror so they can understand & digest thoroughly?

Is this any goddam way to run a justice system?@cspan @cspanwj pic.twitter.com/AIiJElSENY

— Steve 💙🇺🇸 🇹🇷 🇺🇦 (@EnragedApostate) May 29, 2024

But now let me bring it home….

Let’s actually READ them all together, shall we?

I think you’re going to be absolutely overwhelmed….let’s play a game and you tell me how far you were able to get simply memorizing all of this, knowing you would not be able to read it again.

Ready?

From the source here: https://www.nycourts.gov/LegacyPDFS/press/PDFs/People%20v.%20DJT%20Jury%20Instructions%20and%20Charges%20FINAL%205-23-24.pdf

Here we go:

Post-Summation Instructions

Introduction

Members of the jury, I will now instruct you on the law. I will first review the general principles of law that apply to this case and all criminal cases.

You have heard me explain some of those principles at the beginning of the trial. I am sure you can appreciate the benefits of repeating those instructions at this stage of the proceedings.

Next, I will define the crimes charged in this case, explain the law that applies to those definitions, and spell out the elements of each charged crime.

Finally, I will outline the process of jury deliberations.

These instructions will take at least an hour, and you will not receive copies of them. You may however, request that I read them back to you in whole or in part as many times as you wish, and I will be happy to do so.

Role of Court and Jury

During these instructions, I will not summarize the evidence. If necessary, I may refer to portions of the evidence to explain the law that relates to it. My reference to evidence, or my decision not to refer to evidence, expresses no opinion about the truthfulness, accuracy, or importance of any particular evidence. In fact, nothing I have said in the course of this trial was meant to suggest that I have an opinion about this case. If you have formed an impression that I do have an opinion, you must put it out of your mind and disregard it.

The level of my voice or intonation may vary during these instructions. If I do that, it is done to help you understand. It is not done to communicate any opinion about the law or the facts of the case or of whether the defendant is guilty or not guilty.

It is not my responsibility to judge the evidence here. It is yours. You are the judges of the facts, and you are responsible for deciding whether the defendant is guilty or not guilty.

Reminder: Fairness

Remember, you have promised to be a fair juror. A fair juror is a person who will keep their promise to be fair and impartial and who will not permit the verdict to be influenced by a bias or prejudice in favor of or against a person who appeared in this trial on account of that person’s race, color, national origin, ancestry, gender, gender identity or expression, religion, religious practice, age, disability or sexual orientation, and further, a fair juror must be mindful of any stereotypes or attitudes about people or about groups of people that the juror may have, and must not allow those stereotypes or attitudes to affect their verdict.

As I have explained, we all develop and hold unconscious views on many subjects. Some of those unconscious views may come from stereotypes and attitudes about people or groups of people that may impact on a person’s thinking and decision-making without that person even knowing it. As a juror, you are asked to make a very important decision about another member of the community. I know you would not want to make that decision based on such stereotypes or attitudes, that is, on what we call implicit biases, and it would be wrong for you to do so. A fair juror must guard against the impact of such stereotypes or attitudes. You can do this by asking yourself during your deliberations whether your views and conclusions would be different if the defendant, witnesses or others that you have heard about or seen in court were of a different race, color, national origin, ancestry, gender, gender identity or expression, religious practice, age or sexual orientation, or if they did not have a disability. If the answer is yes, then, in keeping with your promise to be fair, reconsider your views and conclusions along with the other jurors, and make sure your verdict is based on the evidence and not on stereotypes or attitudes. Justice requires no less.

Limiting Instruction Regarding the Defendant

Jurors, you will recall that during jury selection you agreed that you would set aside any personal opinions or bias you might have in favor of or against the Defendant, and that you would decide this case fairly on the evidence and the law. Again, I direct you to decide this case on the evidence and the law as it relates to the Defendant here on trial. You must set aside any personal opinions or bias you might have in favor of or against the Defendant, and you must not allow any such opinions to influence your verdict.

Sentence: Not Consider

Remember also, in your deliberations, you may not consider or speculate about matters relating to sentence or punishment. If there is a verdict of guilty, it will be my responsibility to impose an appropriate sentence.

Evidence

When you judge the facts, you are to consider only the evidence.

The evidence in the case includes:

- the testimony of the witnesses,

- the exhibits that were received in evidence, and

- the stipulations agreed to by the parties. Remember, a stipulation is information the parties have agreed to present to the jury as evidence, without calling a witness to testify.

Testimony which was stricken from the record or to which an objection was sustained must be disregarded by you.

Exhibits that were received in evidence are available, upon your request, for your inspection and consideration.

Exhibits that were just seen during the trial, or marked for identification but not received in evidence, are not evidence, and are thus not available for your inspection and consideration.

But testimony based on those exhibits that were not received in evidence may be considered by you. It is just that the exhibit itself is not available for your inspection and consideration.

Evidentiary Inferences

In evaluating the evidence, you may consider any fact that is proven and any inference which may be drawn from such fact.

To draw an inference means to infer, find, conclude that a fact exists or does not exist based upon proof of some other fact or facts.

For example, suppose you go to bed one night when it is not raining and when you wake up in the morning, you look out your window; you do not see rain, but you see that the street and sidewalk are wet, and that people are wearing raincoats and carrying umbrellas. Under those circumstances, it may be reasonable to infer, that is conclude, that it rained during the night. In other words, the fact of it having rained while you were asleep is an inference that might be drawn from the proven facts of the presence of the water on the street and sidewalk, and people in raincoats and carrying umbrellas.

An inference must only be drawn from a proven fact or facts and then only if the inference flows naturally, reasonably, and logically from the proven fact or facts, not if it is speculative. Therefore, in deciding whether to draw an inference, you must look at and consider all the facts in the light of reason, common sense, and experience.

Redactions

As you know, certain exhibits were admitted into evidence with some portions blacked out or redacted. Those redactions were made to remove personal identifying information and to ensure that only relevant admissible evidence was put before you. You may not speculate as to what material was redacted or why, and you may not draw any inference, favorable or unfavorable against either party, from the fact that certain material has been redacted.

Limiting Instructions

You may recall that I instructed you several times during the trial that certain exhibits were being accepted into evidence for a limited purpose only and that you were not to consider that evidence for any other purpose. Under the law we refer to that as a limiting instruction. I will now remind you of some of the limiting instructions you were given during the trial.

AMI – You will recall that you heard testimony that while David Pecker was an executive at AMI, AMI entered into a non-prosecution agreement with federal prosecutors, as well as a conciliation agreement with the Federal Election Commission (FEC). I remind you that evidence was permitted to assist you, the jury, in assessing David Pecker’s credibility and to help provide context for some of the surrounding events. You may consider that testimony for those purposes only. Neither the non-prosecution agreement, nor the conciliation agreement is evidence of the Defendant’s guilt, and you may not consider them in determining whether the Defendant is guilty or not guilty of the charged crimes.

Michael Cohen – You also heard testimony that the Federal Election Commission (“FEC”) conducted an investigation into the payment to Stormy Daniels and of responses submitted by Michael Cohen and his attorney to the investigation. That evidence was permitted to assist you, the jury, in assessing Michael Cohen’s credibility and to help provide context for some of the surrounding events. You may consider that evidence for those purposes only. Likewise, you will recall that you heard testimony that Michael Cohen pleaded guilty to violating the Federal Election Campaign Act, otherwise known as FECA. I remind you that evidence was permitted to assist you, the jury, in assessing Mr. Cohen’s credibility as a witness and to help provide context for some of the events that followed. You may consider that testimony for those purposes only. Neither the fact of the FEC investigation, Mr. Cohen and his attorney’s responses or the fact that Mr. Cohen pleaded guilty, constitutes evidence of the Defendant’s guilt and you may not consider them in determining whether the Defendant is guilty or not guilty of the charged crimes.

Wall Street Journal News articles – You will recall that certain Wall Street Journal news articles were accepted into evidence during the trial. I remind you now that the articles were accepted and may be considered by you for the limited purpose of demonstrating that the articles were published on or about a certain date and to provide context for the other evidence. The exhibits may not be considered by you as evidence that any of the assertions in the articles is true.

Other hearsay evidence not accepted for its truth – There were other exhibits which contained hearsay and were not accepted for theLimiting Instructions (continued)

Other hearsay evidence not accepted for its truth – There were other exhibits which contained hearsay and were not accepted for the truth of the matter asserted but for another purpose. For example, there were several National Enquirer headlines and an invoice from Investor Advisory Services (People’s 161). Those were accepted for the limited purpose of demonstrating that the articles were published and the document created.

There were also some text messages that were accepted with a similar limitation. For example, People’s Exhibit 171.A with respect to Gina Rodriguez’s texts only and 257 with respect to Chris Cuomo’s texts only. Those text messages were accepted for the limited purpose of providing context for the responses by Dylan Howard and Michael Cohen.

The exhibits which were accepted into evidence with a limiting instruction are 152, 153.A, 153.B, 153.C, 161, 171.A, 180, 181 and 257.

If you have any additional questions or need clarification as to which exhibits were accepted into evidence with limitations, just send me a note with your question and I will be happy to clarify.

Presumption of Innocence

We now turn to the fundamental principles of our law that apply in all criminal trials – the presumption of innocence, the burden of proof, and the requirement of proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

Throughout these proceedings, the defendant is presumed to be innocent. As a result, you must find the defendant not guilty, unless, on the evidence presented at this trial, you conclude that the People have proven the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

In determining whether the People have satisfied their burden of proving the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, you may consider all the evidence presented, whether by the People or by the defendant. In doing so, however, remember that, even though the defendant introduced evidence, the burden of proof remains on the People.

Defendant Did Not Testify

The fact that the defendant did not testify is not a factor from which any inference unfavorable to the defendant may be drawn.

Burden of Proof

The defendant is not required to prove that he is not guilty. In fact, the defendant is not required to prove or disprove anything. To the contrary, the People have the burden of proving the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. That means, before you can find the defendant guilty of a crime, the People must prove beyond a reasonable doubt every element of the crime including that the defendant is the person who committed that crime. The burden of proof never shifts from the People to the defendant. If the People fail to satisfy their burden of proof, you must find the defendant not guilty and if the People satisfy their burden of proof, you must find the defendant guilty.

Reasonable Doubt

What does our law mean when it requires proof of guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt”?

The law uses the term, “proof beyond a reasonable doubt,” to tell you how convincing the evidence of guilt must be to permit a verdict of guilty. The law recognizes that, in dealing with human affairs, there are very few things in this world that we know with absolute certainty. Therefore, the law does not require the People to prove a defendant guilty beyond all possible doubt. On the other hand, it is not sufficient to prove that the defendant is probably guilty. In a criminal case, the proof of guilt must be stronger than that. It must be beyond a reasonable doubt.

A reasonable doubt is an honest doubt of the defendant’s guilt for which a reason exists based upon the nature and quality of the evidence. It is an actual doubt, not an imaginary doubt. It is a doubt that a reasonable person, acting in a matter of this importance, would be likely to entertain because of the evidence that was presented or because of the lack of convincing evidence.

Proof of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt is proof that leaves you so firmly convinced of the defendant’s guilt that you have no reasonable doubt of the existence of any element of the crime or of the defendant’s identity as the person who committed the crime.

In determining whether the People have proven the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, you should be guided solely by a full and fair evaluation of the evidence. After carefully evaluating the evidence, each of you must decide whether that evidence convinces you beyond a reasonable doubt of the defendant’s guilt.

Whatever your verdict may be, it must not rest upon baseless speculation. Nor may it be influenced in any way by bias, prejudice, sympathy, or by a desire to bring an end to your deliberations or to avoid an unpleasant duty.

If you are not convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty of a charged crime, you must find the defendant not guilty of that crime and if you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty of a charged crime, you must find the defendant guilty of that crime.

Credibility of Witnesses

Introduction

As judges of the facts, you alone determine the truthfulness and accuracy of the testimony of each witness.

You must decide whether a witness told the truth and was accurate, or instead, testified falsely or was mistaken. You must also decide what importance to give to the testimony you accept as truthful and accurate. It is the quality of the testimony that is controlling, not the number of witnesses who testify.

Accept in Whole or in Part (Falsus in Uno)

If you find that any witness has intentionally testified falsely as to any material fact, you may disregard that witness’s entire testimony. Or, you may disregard so much of it as you find was untruthful, and accept so much of it as you find to have been truthful and accurate.

Credibility Factors

There is no particular formula for evaluating the truthfulness and accuracy of another person’s statements or testimony. You bring to this process all of your varied experiences. In life, you frequently decide the truthfulness and accuracy of statements made to you by other people. The same factors used to make those decisions, should be used in this case when evaluating the testimony.

In General

Some of the factors that you may wish to consider in evaluating the testimony of a witness are as follows:

- Did the witness have an opportunity to see or hear the events about which he or she testified?

- Did the witness have the ability to recall those events accurately?

- Was the testimony of the witness plausible and likely to be true, or was it implausible and not likely to be true?

- Was the testimony of the witness consistent or inconsistent with other testimony or evidence in the case?

- Did the manner in which the witness testified reflect upon the truthfulness of that witness’s testimony?

- To what extent, if any, did the witness’s background, training, education, or experience affect the believability of that witness’s testimony?

- Did the witness have a conscious bias, hostility or some other attitude that affected the truthfulness of the witness’s testimony?

- Did the witness show an “unconscious bias,” that is, a bias that the witness may have even unknowingly acquired from stereotypes and attitudes about people or groups of people, and if so, did that unconscious bias impact that witness’s ability to be truthful and accurate?

Motive

You may consider whether a witness had, or did not have, a motive to lie.

If a witness had a motive to lie, you may consider whether and to what extent, if any, that motive affected the truthfulness of that witness’s testimony.

If a witness did not have a motive to lie, you may consider that as well in evaluating the witness’s truthfulness.

Benefit

You may consider whether a witness hopes for or expects to receive a benefit for testifying. If so, you may consider whether and to what extent it affected the truthfulness of the witness’s testimony.

Interest/Lack of Interest

You may consider whether a witness has any interest in the outcome of the case, or instead, whether the witness has no such interest.

You are not required to reject the testimony of an interested witness, or to accept the testimony of a witness who has no interest in the outcome of the case.

You may, however, consider whether an interest in the outcome, or the lack of such interest, affected the truthfulness of the witness’s testimony.

Previous Criminal Conduct

You may consider whether a witness has been convicted of a crime or has engaged in criminal conduct, and if so, whether and to what extent it affects your evaluation of the truthfulness of that witness’s testimony.

You are not required to reject the testimony of a witness who has been convicted of a crime or has engaged in criminal conduct, or to accept the testimony of a witness who has not.

You may, however, consider whether a witness’s criminal conviction or conduct has affected the truthfulness of the witness’s testimony.

Inconsistent Statements

You may consider whether a witness made statements at this trial that are inconsistent with each other.

You may also consider whether a witness made previous statements that are inconsistent with his or her testimony at trial.

You may consider whether a witness testified to a fact here at trial that the witness omitted to state, at a prior time, when it would have been reasonable and logical for the witness to have stated the fact. In determining whether it would have been reasonable and logical for the witness to have stated the omitted fact, you may consider whether the witness’ attention was called to the matter and whether the witness was specifically asked about it.

If a witness has made such inconsistent statements or omissions, you may consider whether and to what extent they affect the truthfulness or accuracy of that witness’s testimony here at this trial.

The contents of a prior inconsistent statement are not proof of what happened. You may use evidence of a prior inconsistent statement only to evaluate the truthfulness or accuracy of the witness’s testimony here at trial.

Consistency

You may consider whether a witness’s testimony is consistent with the testimony of other witnesses or with other evidence in the case.

If there were inconsistencies by or among witnesses, you mayRole of Court and Jury (continued)

If there were inconsistencies by or among witnesses, you may consider whether they were significant inconsistencies related to important facts, or instead were the kind of minor inconsistencies that one might expect from multiple witnesses to the same event.

Witness Pre-trial Preparation

You have heard testimony about the prosecution and defense counsel speaking to a witness about the case before the witness testified at this trial. The law permits the prosecution and defense counsel to speak to a witness about the case before the witness testifies, and permits a prosecutor and defense counsel to review with the witness the questions that will or may be asked at trial, including the questions that may be asked on cross-examination.

You have also heard testimony that a witness read or reviewed certain materials pertaining to this case before the witness testified at trial. The law permits a witness to do so.

Speaking to a witness about his or her testimony and permitting the witness to review materials pertaining to the case before the witness testifies is a normal part of preparing for trial. It is not improper as long as it is not suggested that the witness depart from the truth.

Identification

The People have the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt, not only that a charged crime was committed, but that the defendant is the person who committed that crime.

Thus, even if you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that a charged crime was committed by someone, you cannot convict the defendant of that crime unless you are also convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that he is the person who committed that crime.

Accomplice as a Matter of Law

Under our law, Michael Cohen is an accomplice because there is evidence that he participated in a crime based upon conduct involved in the allegations here against the defendant.

Our law is especially concerned about the testimony of an accomplice who implicates another in the commission of a crime, particularly when the accomplice has received, expects or hopes for a benefit in return for his testimony.

Therefore, our law provides that a defendant may not be convicted of any crime upon the testimony of an accomplice unless it is supported by corroborative evidence tending to connect the defendant with the commission of that crime.

In other words, even if you find the testimony of Michael Cohen to be believable, you may not convict the defendant solely upon that testimony unless you also find that it was corroborated by other evidence tending to connect the defendant with the commission of the crime.

The corroborative evidence need not, by itself, prove that a crime was committed or that the defendant is guilty. What the law requires is that there be evidence that tends to connect the defendant with the commission of the crime charged in such a way as may reasonably satisfy you that the accomplice is telling the truth about the defendant’s participation in that crime.

In determining whether there is the necessary corroboration, you may consider whether there is material, believable evidence, apart from the testimony of Michael Cohen, which itself tends to connect the defendant with the commission of the crime.

You may also consider whether there is material, believable evidence, apart from the testimony of Michael Cohen, which, while it does not itself tend to connect the defendant with the commission of the crime charged, it nonetheless so harmonizes with the narrative of the accomplice as to satisfy you that the accomplice is telling the truth about the defendant’s participation in the crime and thereby tends to connect the defendant to the commission of the crime.

The Charged Crimes

I will now instruct you on the law applicable to the charged offenses.

That offense is Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree – 34 Counts.

Accessorial Liability

Our law recognizes that two or more individuals can act jointly to commit a crime, and that in certain circumstances, each can be held criminally liable for the acts of the others. In that situation, those persons can be said to be “acting in concert” with each other.

Our law defines the circumstances under which one person may be criminally liable for the conduct of another. That definition is as follows:

When one person engages in conduct which constitutes an offense, another is criminally liable for such conduct when, acting with the state of mind required for the commission of that offense, he or she solicits, requests, commands, importunes, or intentionally aids such person to engage in such conduct.

Under that definition, mere presence at the scene of a crime, even with knowledge that the crime is taking place, or mere association with a perpetrator of a crime, does not by itself make a defendant criminally liable for that crime.

In order for the defendant to be held criminally liable for the conduct of another which constitutes an offense, you must find beyond a reasonable doubt:

- That he solicited, requested, commanded, importuned, or intentionally aided that person to engage in that conduct, and

- That he did so with the state of mind required for the commission of the offense.

If it is proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant is criminally liable for the conduct of another, the extent or degree of the defendant’s participation in the crime does not matter. A defendant proven beyond a reasonable doubt to be criminally liable for the conduct of another in the commission of a crime is as guilty of the crime as if the defendant, personally, had committed every act constituting the crime.

The People have the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant acted with the state of mind required for the commission of the crime, and either personally, or by acting in concert with another person, committed each of the remaining elements of the crime.

Your verdict, on each count you consider, whether guilty or not guilty, must be unanimous. In order to find the defendant guilty, however, you need not be unanimous on whether the defendant committed the crime personally, or by acting in concert with another, or both.

The Charged Crimes (continued)

I will now instruct you on the law applicable to the charged offense. That offense is Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree – 34 Counts.

Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree Penal Law § 175.10

Under our law, a person is guilty of falsifying business records in the first degree when, with intent to defraud that includes an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof, that person:

- makes or causes a false entry in the business records of an enterprise.

The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning:

Enterprise means any entity of one or more persons, corporate or otherwise, public or private, engaged in business, commercial, professional, industrial, social, political or governmental activity.

Business Record means any writing or article, including computer data or a computer program, kept or maintained by an enterprise for the purpose of evidencing or reflecting its condition or activity.

Intent means conscious objective or purpose. Thus, a person acts with intent to defraud when his or her conscious objective or purpose is to do so. Intent does not require premeditation. In other words, intent does not require advance planning. Nor is it necessary that the intent be in a person’s mind for any particular period of time. The intent can be formed, and need only exist, at the very moment the person engages in prohibited conduct or acts to cause the prohibited result, and not at any earlier time.

The question naturally arises as to how to determine whether a defendant had the intent required for the commission of a crime.

To make that determination in this case, you must decide if the required intent can be inferred beyond a reasonable doubt from the proven facts.

In doing so, you may consider the person’s conduct and all of the circumstances surrounding that conduct, including, but not limited to, the following:

- what, if anything, did the person do or say;

- what result, if any, followed the person’s conduct; and

- was that result the natural, necessary and probable consequence of that conduct.

Therefore, in this case, from the facts you find to have been proven, decide whether you can infer beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant had the intent required for the commission of this crime.

Intent to Defraud

As I previously explained, a person acts with intent to defraud when his or her conscious objective or purpose is to do so.

In order to prove an intent to defraud, the People need not prove that the defendant acted with the intent to defraud any particular person or entity. A general intent to defraud any person or entity suffices.

Intent to defraud is also not constricted to an intent to deprive another of property or money and can extend beyond economic concerns.

Intent to Commit or Conceal Another Crime

For the crime of Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree, the intent to defraud must include an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof.

Under our law, although the People must prove an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof, they need not prove that the other crime was in fact committed, aided, or concealed.

New York Election Law § 17-152 Predicate

The People allege that the other crime the defendant intended to commit, aid, or conceal is a violation of New York Election Law section 17-152.

Section 17-152 of the New York Election Law provides that any two or more persons who conspire to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means and which conspiracy is acted upon by one or more of the parties thereto, shall be guilty of conspiracy to promote or prevent an election.

Under our law, a person is guilty of such a conspiracy when, with intent that conduct be performed that would promote or prevent the election of a person to public office by unlawful means, he or she agrees with one or more persons to engage in or cause the performance of such conduct.

Knowledge of a conspiracy does not by itself make the defendant a coconspirator. The defendant must intend that conductNew York Election Law § 17-152 Predicate (continued)

Knowledge of a conspiracy does not by itself make the defendant a coconspirator. The defendant must intend that conduct be performed that would promote or prevent the election of a person to public office by unlawful means. Intent means conscious objective or purpose. Thus, a person acts with the intent that conduct be performed that would promote or prevent the election of a person to public office by unlawful means when his or her conscious objective or purpose is that such conduct be performed.

Evidence that the defendant was present when others agreed to engage in the performance of a crime does not by itself show that he personally agreed to engage in the conspiracy.

“By Unlawful Means”

Although you must conclude unanimously that the defendant conspired to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means, you need not be unanimous as to what those unlawful means were.

In determining whether the defendant conspired to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means, you may consider the following: (1) violations of the Federal Election Campaign Act otherwise known as FECA; (2) the falsification of other business records; or (3) violation of tax laws.

The Federal Election Campaign Act

The first of the People’s theories of “unlawful means” which I will now define for you is the Federal Election Campaign Act.

Under the Federal Election Campaign Act, it is unlawful for an individual to willfully make a contribution to any candidate with respect to any election for federal office, including the office of President of the United States, which exceeds a certain limit. In 2015 and 2016, that limit was $2,700. It is also unlawful under the Federal Election Campaign Act for any corporation to willfully make a contribution of any amount to a candidate or candidate’s campaign in connection with any federal election, or for any person to cause such a corporate contribution. For purposes of these prohibitions, an expenditure made in cooperation, consultation, or concert with, or at the request or suggestion of, a candidate or his agents shall be considered to be a contribution to such candidate.

The terms CONTRIBUTION and EXPENDITURE include anything of value, including any purchase, payment, loan, or advance, made by any person for the purpose of influencing any election for federal office.

Under federal law, a third party’s payment of a candidate’s expenses is deemed to be a contribution to the candidate unless the payment would have been made irrespective of the candidacy.

If the payment would have been made even in the absence of the candidacy, the payment should not be treated as a contribution.

FECA’s definitions of “contribution” and “expenditure” do not include any cost incurred in covering or carrying a news story, commentary, or editorial by a magazine, periodical publication, or similar press entity, so long as such activity is a normal, legitimate press function. This is called the press exemption. For example, the term legitimate press function includes solicitation letters seeking new subscribers to a publication.

Join the conversation!

Please share your thoughts about this article below. We value your opinions, and would love to see you add to the discussion!